Hazaristan Charter

Hazara According to the Hazaristan Charter

According to the Hazaristan Charter, Article 19, "Any person born to a Hazara parent, whether in Hazaristan or outside Hazaristan, is a Hazara, Hazaristani, and a citizen of Hazaristan."

This definition of the Hazara makes it easier to have protocols for the Identity Holder to request credentials and for Identity Issuer (Digital Hazaristan) to issue in the process of identity construction within the Ecosystem of Digital Hazaristan.

According to the Hazaristan Charter, Article 19, "Any person born to a Hazara parent, whether in Hazaristan or outside Hazaristan, is a Hazara, Hazaristani, and a citizen of Hazaristan."

This definition of the Hazara makes it easier to have protocols for the Identity Holder to request credentials and for Identity Issuer (Digital Hazaristan) to issue in the process of identity construction within the Ecosystem of Digital Hazaristan.

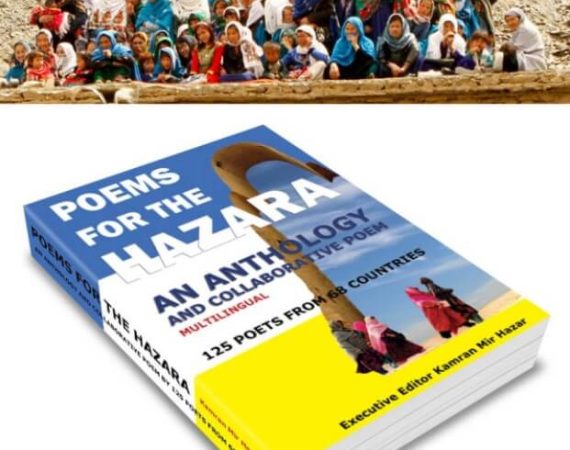

Japanese Poet and Director of the World Haiku Association Ban'ya Natsuishi

The Hazara people of central Asia overlapped various cultures; they enriched our civilization.

Background Information

The Hazara Stateless Nation

With Asian roots and almond eyes, the Hazara were the largest ethnic group in their country before the Afghan/Pashtun tribes' attacks and massacring more than 60% (Minority Rights, 2015). The borders of the Hazara territory, known as Hazaristan, the land of Dai-s, were "in one direction from Kandahar in the south to Mazar-i-Sharif in the north and another direction from Kabul in the east to Herat in the west" (Bellew, 1880, pp. 113-117).

With Asian roots and almond eyes, the Hazara were the largest ethnic group in their country before the Afghan/Pashtun tribes' attacks and massacring more than 60% (Minority Rights, 2015). The borders of the Hazara territory, known as Hazaristan, the land of Dai-s, were "in one direction from Kandahar in the south to Mazar-i-Sharif in the north and another direction from Kabul in the east to Herat in the west" (Bellew, 1880, pp. 113-117).

Backed by British colonial officers, as the attacks from northern parts of British India increased and the Hazara Dais were invaded by Afghans (Mir Hazar, 2020a; Poets Worldwide, 2017; Temirkhanov, 1980, pp. 259-260), the name of Afghanistan appeared on the maps (Vivien de St Martin, 1825). According to historians and the day’s newspapers, thousands of the Hazara captives, including women and children, were also sold as slaves (Poets Worldwide, 2017, p. 257; Temirkhanov, 1980; Thames Star, 1892; Waikato Times, 1892); the most parts of invaded Dais were distributed among the attackers, and many Hazara forced to work on their own lands for the invaders (Katib Hazārah, 2016, p. 969; Temirkhanov, 1980, pp. 265-266).

The “entire 20th-century history has been marked by killings of Hazara and systematic discrimination against them” (Poets Worldwide, 2017, p. 257). For instance, in the last decade of the 20th century, the Afghan Taliban massacred thousands of the Hazara in Mazar-i-Sharif, Yakawlang, Bamyan, and Koudiposht (Human Rights Watch, 1998; Poets Worldwide, 2017). The main policy of the “Taliban’s ethnocratic and clerical regime” was/is to force other ethnic groups such as the Uzbek, Tajik, and Turkmen out to Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan and the Hazara to the graveyard (Mir Hazar, 2020b; Zabriskie, 2008). Falsifying and destroying the Hazara history, culture and identity was another parallel plan that has been flowed besides other systematic crimes. For instance, in 2001, the “Taliban destroyed the ancient Buddha sculptures of Bamyan, which were principal symbols of Hazara history and culture and one of the most popular masterpieces of the oral and intangible heritage of humanity” (Human Rights Watch, 1998; Poets Worldwide, 2017).

In the 21st century, the Hazara resistance tried harder to change their human rights situation by improving education, gender equality, and establishing civil rights movements. However, the systematic crimes against them did not end. The Taliban and other fundamental ethnocratic and clerical groups are still targeting, abducting, and beheading them, and the Afghani regimes isolate their protests and legalize discrimination against them. “For instance, in July 2016, the Hazara Enlightenment Movement’s peaceful protest targeted by the Taliban-Daesh, after the regime forcefully isolates the rally in one part of Kabul, which in addition to the massacre, as the president of PEN International, Jennifer Clement, explains, it should also be considered censorship (Mir Hazar, 2020b, 2020c; Poets Worldwide, 2017)”.

In the era of the internet and social media, identity has been one of the hottest topics among non-Afghans/Pashtuns, including the Hazara (Lewis, 2011). Many of them question not only Afghan as their national identity and Afghanistan as the name of their country, but also the issue of majority and minority, arguing that the dominant group that has power for decades broadcast false information in the absence of a comprehensive census and based on unreliable data and narration (Raofi, 2018).

In 2021, a group of Hazara intellectuals under The Pioneers of the Hazaristan Independence Movement (2021) released the Charter of Hazaristan. In the third article of this charter under chapter one, one of the goals is to “form a Digital Hazaristan and establish high security and privacy-protected digital identity along with issuing a national identification number and conducting a census of Hazaristan citizens.”

Source:

Kamran Mir Hazar |

Hazara Digital Identity, a Human Right by Default

By default, every Hazara has the right to have a Digital Identity and National Identification Number within the ecosystem of Digital Hazaristan/e-Hazaristan.